A Look at Slowflyers and Parkflyers

November 1, 2002 for Sailplane & Electric Modeler Magazine

Slowflyer and Parkflyer models have taken the electric aircraft world by storm, or rather, by gentle breeze. There are no official definitions of what constitutes a slowflyer or parkflyer, so I will make some up.

A slowflyer is a model airplane that flies slowly enough to be comfortably flown in a gymnasium or similar large building, although it need not be flown inside. Almost out of necessity, such a model would have to be electrically powered since the noise and fumes would be intolerable indoors (although a CO2 powered model might qualify).

A parkflyer is one step up from a slowflyer. It is too fast to fly in readily available indoor spaces, but can be flown from a relatively small field as might be found in a park or schoolyard. Although there are some glow powered parkflyers on the market, there are probably few parks where they would be tolerated.

The distinction between slowflyer and parkflyer is blurry, since any slowflyer can be flown outdoors in sufficiently calm conditions. Likewise, any parkflyer can be flown indoors given a sufficiently large building; even a fast Speed 400 model could probably be flown in a 747 hangar (as long as the 747 isn’t home).

What Makes it Slow?

The most significant factor making a slowflyer slow enough to fly indoors is wing loading. Many indoor models have 3- or 4-foot wing spans, with 200 to 400 square inches of wing area, yet weigh only 7 or 8 ounces. For example, my GWS Pico Stick, a popular almost-ready-to-fly (ARF) slowflyer, weighs 8 ounces and has 236 square inches (1.64 square feet) of wing, giving a wing loading of about 4.9 oz/sq.ft. My friend’s Ikarus Bleriot II is even bigger (3.35 square feet), and at only 7 ounces, has a 2.1 oz/sq.ft wing loading.

Using the approximate stall speed formula of 4 times the square root of the wing loading, these two models will stall at about 9 mph and 6 mph respectively. Flying 100 foot diameter circles at just above stall speed will take about 24 seconds and 36 seconds respectively, which feels quite slow, even indoors.

Of course, flying just above stall speed is a bit nerve wracking, since a small mistake can cause a stall and crash. So, we fly them a bit faster for comfort. But if you’re thinking you can put the nose down, apply full power, and hot-dog around the gym, think again, because there is drag to contend with.

Most slowflyers have very thin, under-cambered, high lift airfoils. In addition to producing a lot of lift at low speeds, these airfoils also produce a lot of drag. At the low power levels typical of a slowflyer, this drag limits the maximum speed. I haven’ t taken measurements, but I’d estimate this maximum to be around 1.5 to 2 times the stall speed. So even our 9 mph stalling slowflyer would have a top speed of less than 18 mph, which still gives a whole 12 seconds for our 100 ft circles.

A great way to demonstrate the high drag of a slowflyer is to attempt to do a loop. Take the plane up to about 30 feet, dive fairly steeply to about 10 feet, and try to loop. You’ll be lucky if the model makes it more than a quarter of the way up the first half of the loop before stalling.

Why is it Fun?

Or rather, why is it not nerve-wracking? A regular "sport" type model, whether powered by a Speed 400 motor, or a 500 Watt brushless setup, would not be much fun to fly if its top speed was only 1.5 times its stall speed.

If you want to see what this is like, try flying a direct-drive Speed 400 or 600 powered model with a propeller of 10% larger diameter and 30% lower pitch than you’d usually use. For example, use a 9×3 on a model that normally flies well with an 8×4. You’ll find take-off performance about the same as usual, but the model will be struggling to remain airborne, with a narrow margin between stall speed and maximum speed. (Note: don’t really try this, or you’ll likely lose your plane in a stall-spin accident). Many beginner 2-meter electric sailplanes with cheap direct-drive power systems fly like this, which in the past, has probably been the main reason electrics had a bad reputation.

So, why do we not suffer these poor flight characteristics with slowflyers? The answer is, that we sometimes do. What makes this tolerable is that everything happens so slowly. When the plane slows down and is about to stall, we can react fast enough to prevent it.

The high drag also saves us here. With a typical sport model, if we find it always pitching up, slowing down, and stalling, we just dial in some down-elevator trim. If we dial in too much trim, the model might fly too fast for our skill or comfort level. A high-drag slowflyer on the other hand will still fly rather slowly, even if we trim it for a dive. It’s easy to take the time to adjust the trim and get everything working smoothly, because even when it’s diving fast, it’s still going pretty slow.

These two Speed 400 powered models could be flown in a schoolyard, soccer field, or park. The GravelMaster, on the left, is a bit fast, but quite maneuverable. The Sydney’s Special is a bit lighter and larger, making for a slower flying model.

Choosing a Slowflyer or Parkflyer

As we’ve discussed above, slowflyers and parkflyers have low wing loadings, in the 2 to 5 ounce per square foot range. The lower the slower. If you’re an inexperienced pilot, something near the lower end of this range is a good choice for indoor flying. With a bit of experience, a model near the high end of the range is also readily flown indoors.

Parkflyers need to have slightly higher wing loadings. Although slowflyers can be flown outdoors, the very light ones don’t do well in anything but calm conditions. My Pico Stick will handle winds of up to about 3 mph, beyond which flying isn’t fun any more. The plane gets blown around too much. A wing loading range of 6 to 9 ounces per square foot (for a 3- to 4-foot span model) is more suitable.

This Diversity Models Dragonfly is a Speed 400 powered parkflyer. It could be flown indoors, but is a little fast for comfort.

Most models powered by a geared Speed 280 motor or a direct-drive or geared Speed 400 motor, and a 6- or 7-cell battery pack, are suitable for flying in parks having open areas the size of a soccer field. Exceptions would be small fast models, like my Flit or a Speed 400 class pylon racer, or if there’s any wind, extremely light models like the Bleriot II. Use the wing loading as a guide: 6 to 7 oz/sq.ft for Speed 280 power, and 7 to 9 oz/sq.ft for Speed 400 power.

Radio Equipment

Remember that lighter is generally better for slowflyers and parkflyers. Therefore, choose the lightest radio equipment you can find. I use a Hitec Feather receiver in my Pico Stick, and my friend uses a JR 610 in his Bleriot II.

The Feather is a single-conversion receiver, not intended for long range or busy flying fields, but it is well suited to the solitary close-in flying that one does with a slowflyer or parkflyer. The 610 is a full-fledged receiver, only slightly bigger and heavier than the Feather, and would be my choice if flying in a group setting.

Use the lightest possible servos too, especially in slowflyers. Although some of the smaller servos have very little torque, not much is needed in such light slow flying models. My friend and I both use Hitec HS-55 servos in our slowflyers. At 8 grams (0.34 oz), these are no longer the very lightest, but they are readily available and inexpensive.

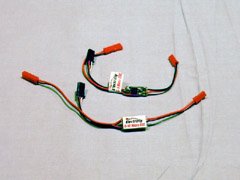

The Great Planes Electrifly C-5 (top) and C-10 speed controls are rated at 5 and 10 Amps respectively, and are equipped with a batter eliminator circuit (BEC). The C-5 is ideal for slowflyers using up to a Speed 280 motor. The C-10 can handle many Speed 400 applications.

The last piece of equipment is the electronic speed control (ESC). Because of the low currents in slowflyer models, these have become very small and light. By far the heaviest parts are the wires and connectors. You can save some weight by cutting off the motor connector, cutting the leads to just the right length, and soldering them directly to the motor. All slowflyer ESCs have a battery eliminator circuit (BEC) so that it is not necessary to have a separate receiver battery, which would be a serious weight penalty in such a small model. I used the 6 gram (0.21 oz) Great Planes ElectriFly C-5 in my Pico Stick, and my friend uses the C-10 in his Bleriot II. The C-10 is probably overkill, but it was handy and weighs only 8 grams (0.27 oz).

When smaller models first became popular (the Speed 400 craze that started a few years back), small equipment (such as 14 gram / 0.5 oz servos) was very expensive. Now, slowflyer and parkflyer models account for a significant portion of the R/C economy, and these items are almost as cheap as their standard-sized counterparts.

Some of the slowflyer manufacturers also produce equipment to use with their models. For example, GWS produces the GWR4 Pico series of receivers, and the Pico and Naro servos (I’m convinced the latter were meant to be called "Nano", and that somewhere early on, someone made a typo and the name "Naro" stuck). The Pico servos weigh only 5.4 grams (0.19 oz).

Safety

Because slowflyers and parkflyers are often flown in areas that aren’t designated radio control (R/C) flying fields, there are some additional safety precautions to consider.

First and foremost is the safety of spectators. Although a Bleriot or Pico Stick is not likely to hurt someone, it is possible. Even at a few miles an hour, and even with a soft rubber or plastic spinner, a direct hit in the eye of a bystander is going to cause serious injury. And some parkflyer models can fly quite a bit faster, increasing the odds of hurting someone or damaging property.

Another issue is that of interference with other R/C activity. Because slowflyers and parkflyers are flown in public areas, and often by people with no other R/C experience, there is the potential of interference with a nearby R/C field. Slowflyers and parkflyers use the same frequencies as larger, heavier, and faster R/C models. If a nearby R/C modeler is flying on the same frequency as your slowflyer, your model is unlikely to be damaged in the resulting crash, but the larger model will almost certainly be destroyed and/or cause damage or injury. Before flying in a park or building, make sure there is no R/C field within five miles of your intended flying site.

If you are a manufacturer or reseller of slowflyers or parkflyers, I ask you to include with your models a warning about the potential hazards of injuring bystanders, and of interfering with the safe operation of more powerful and potentially dangerous R/C models.

Slow is Relaxing

Although I normally fly slightly larger models, I find a slowflyer to be fun and relaxing. Everything happens so slowly that there’s usually plenty of time to react. And when a mistake is made, the resulting crash rarely results in any damage. Even if you’re into giant scale, I’d highly recommend a slowflyer in your fleet for those days when you just want to take it easy.

Related Articles

If you've found this article useful, you may also be interested in:

If you've found this article useful, consider leaving a donation in Stefan's memory to help support stefanv.com

Disclaimer: Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and reliability, the information on this web page is presented without warranty of any kind, and Stefan Vorkoetter assumes no liability for direct or consequential damages caused by its use. It is up to you, the reader, to determine the suitability of, and assume responsibility for, the use of this information. Links to Amazon.com merchandise are provided in association with Amazon.com. Links to eBay searches are provided in association with the eBay partner network.

Copyright: All materials on this web site, including the text, images, and mark-up, are Copyright © 2025 by Stefan Vorkoetter unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved. Unauthorized duplication prohibited. You may link to this site or pages within it, but you may not link directly to images on this site, and you may not copy any material from this site to another web site or other publication without express written permission. You may make copies for your own personal use.

Rob Beale

January 30, 2008

Very interesting article and a good introduction to both subjects. I particularly like the information on stall speeds/wing-loading and its calculations. Any other simple but handy rule of thumb ratios and calculations are useful when designing your own planes.

Look forward to reading some more articles from you.

Rob

Stefan Vorkoetter

January 30, 2008

Rob, you’ll probably be interested in my "Electric Flight Rules of Thumb" article: http://www.stefanv.com/rcstuff/qf200407.html