What to Put in Your Field Box

October 1, 2001 for Sailplane & Electric Modeler Magazine

As electric flyers, our requirements for a field box are different than those of glow fliers. This month, I’m going to go over the typical contents of my field box, telling you what’s in it and why. I’m not going to cover the design of the bo, since I’m not convinced that the one I’ve built is anywhere near optimal (although I find it more suitable than any of the glow-oriented boxes on the market).

The Essentials

There are really only a few essential things that you must have in your field box.

This is my main field box, which can hold almost everything in the checklist, including two transmitters. It’s a little bit crowded, but does the job. Originally, the handle extended past one end, and held my hi-start reel from my glider flying days.

I often go flying at lunch time with a colleague from work, so I keep a plane and a minimal field box in the office all the time. It contains a transmitter, three 7-cell RC2000 packs, spare wing and landing gear bolts, and a screwdriver. This is all we need for 40 minutes to an hour at the local field. If we don’t break anything, even the bolts and screwdriver are optional, because we never disassemble the plane.

We charge all the packs at work using a simple home-made AC powered thermal cut-off one-hour charger during the morning, and they’re ready to go by noon.

Unless you own a lot of battery packs, longer flying sessions will require a field charger and a 12V lead-acid deep-cycle battery to charge from. If you only intend to charge a few packs (no more than about five or six charges of a 7-cell RC2000 pack), you can use your car’s battery without reducing its life span too much.

All of my planes have bolt-on wings, so I carry a generous selection of spare wing bolts in my field box. If your plane uses rubber bands, bring plenty of those too. You won’t need as many as a glow flier though, because you won’t need to replace them after every flight.

Should Have

There are a few other things to bring along that can prevent a flying session from coming to a premature end.

I built this field box out of a dowel, a cardboard box, and some packing tape. It’s very minimal, holding only a transmitter, batteries, wing bolts, a spare prop, and a few tools. This is the box I keep at work and use when flying on my lunch hour.

A not uncommon occurrence is to blow a fuse, usually when belly landing a plane before cutting the throttle, or if the plane noses over during a take-off run. There’s nothing more annoying than having to return home (or drive to the auto-parts store) for a tiny little item that takes almost no room in the box.

The same situations that blow fuses will also often break propellers, especially wooden or carbon fiber props. Keeping a few spare props (and prop adapters, in case you lose the whole assembly in flight) on hand can really prevent a ruined day.

In addition to various spare parts, be sure to bring the tools needed to install them. This includes the appropriate screwdrivers, wrenches, and Allen keys (for prop adapters).

Nice to Have

Now we get into the realm of the nice to have. These are the items you can easily do without, but which can make life at the field easier by helping with troubleshooting or repairs.

When a prop blade does break off, Murphy’s law states that it is likely to go right through the wing. Stiff weeds also have a penchant for poking holes. A roll of good quality clear (or colored) packing tape provides the material to make a temporary repair and get you through the rest of the day.

In the event of structural damage, CA glue (the odorless kind if you’re allergic to CA) and some balsa scraps can often be used to make a field repair, which can then be re-covered with packing tape. An inexpensive hobby knife (the kind with the snap-off blades can often be found for less than $1) is usually handy in these cases too.

Field box electronic equipment, clockwise from top left: home made peak charger, home made expanded scale voltmeter (ESV), GloBee tachometer, and Astroflight Whattmeter.

Although problems with the plane’s electrical system are not all that common (compared with structural or covering damage), they do happen, and there are a few tools that can help you troubleshoot and repair such problems.

An ammeter (or an Astroflight Whattmeter) is handy for diagnosing problems. For example, I once had a plane that kept blowing fuses. Inserting the Whattmeter between the battery and ESC indicated that the current draw was about three times what it used to be. Since the fuse was between the ESC and motor, it was immediately clear that there was something wrong with the motor. On another occasion, the plane’s performance was much lower than usual, and the Whattmeter indicated a fluctuating current draw, which was quickly traced down to a loose connection on the arming switch.

The next most useful piece of diagnostic equipment would be tachometer. This too can help detect performance anomalies, such as a prop that is turning much slower than it used to. Together with the Whattmeter, this can really narrow things down quickly.

When you find an electrical problem, the repair, whether it is fixing a connection, or replacing the motor (if you have a spare on hand), often requires soldering. A butane powered soldering iron is indispensable for this task. I have a 60W one in my field box, and it runs for about one hour on a filling. It’s even strong enough to solder 16ga wires to AR sized cells. Be sure to bring solder too, along with electrical tape to insulate connections.

If your model has a separate receiver pack, using an expanded scale voltmeter (ESV) is good insurance against radio system failure. The ESV can detect a low state of charge, and often problems such as poor connections or nearly broken wires (both of which cause increased resistance, and hence a lower voltage under load at the ESV).

One other tool I keep in my field box, which is really just a luxury, is a cordless screwdriver. Wing and landing gear bolts are not hard to install with a hand screwdriver, but a cordless screwdriver seems less prone to slipping off the screw and puncturing the wing.

A wide-brimmed sun hat is a good idea for summer time flying. A good quality pair of sunglasses is essential for all daylight flying.

Miscellaneous

There are a few other things to put in your field box, or at least bring to the field. The most crucial of these is probably a good pair of sunglasses (see my review of aviator sunglasses). Somewhat paradoxically, this seems to be even more important on overcast days, since the white backdrop of the clouds seems to be brighter than blue sky (except near the sun). I’ve tried a lot of different sunglasses over the years, and have finally settled on Zurich R/C sunglasses. They also fit over most prescription glasses.

In addition to sunglasses, on sunny days a wide-brimmed sun hat is a good idea. The brim will keep light from getting in behind your glasses and causing reflections, and will also keep the sun off your face and neck. As a Canadian, my personal preference is the Tilley hat.

And of course, no day in the sun is complete without a good sunscreen lotion these days. Pick something with a sun-block factor at least 4 or 5 times the number of hours you plan to be in the sun. A word of warning though, don’t apply it above your eyes; I once did this, and it ran into my eyes while flying, blinding me. I managed to crash-land while just barely squinting out of one eye.

If you’re flying in an area with lots of bugs, I’d suggest bringing some bug repellent. I hate spraying the stuff on my skin, so I usually just spray it on the front and back of my shirt, and on my hat, which seems to keep the bugs from biting. There’s nothing worse than being unable to swat away the mosquitoes or black flies because you’re too busy flying.

In the winter, I often wear layered gloves, from inside to outside: ladies’ thin knitted gloves for some insulation, latex surgical gloves to keep the wind out, and thick wool fingerless gloves to keep my hand warm.

For winter flying, a pair of thin but warm gloves is useful. If they’re too thick, it’s hard to work the transmitter sticks, but if they’re too thin, you’ll get cold. There are two hand coverings I’ve found useful. One is a pair of winter English horseback riding gloves, which are thin, provide good grip, and are reasonably warm on calm days (they’re usually quite expensive though, like most things with the word "horse" in their name). The other thing that has worked for me is a three layer concoction of a thin knitted ladies’ glove, covered with a latex surgical glove to cut the wind and provide grip, covered with a thick wool fingerless glove.

If you fly at a club field or a fun fly, someone invariably brings something unique and interesting. For this reason, I almost always bring a camera. One of the new super compact 24mm APS cameras can fit right in your pocket, and takes pictures that are almost as good as those from a good 35mm camera. (Update 2006: these days, I carry a 4 megapixel compact digital camera.)

Finally, it’s always possible for you, or someone else, to get hurt while e-flying, so it’s a good idea to have a first aid kit handy. At the very least, bring a few adhesive bandages.

Checklist

Here’s a checklist of all the items I’ve talked about so far. Use this as the basis for your own checklist, so you don’t forget anything when you go to the field:

-

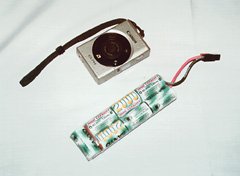

This super-compact APS camera takes excellent pictures at the field or in the club house, and is small enough to keep in your pocket. The battery pack is a 7xRC2000. These days, I use a similarly compact digital camera.

Planes (and their wings)

- Transmitter

- Battery packs

- Charger

- Deep cycle lead-acid battery

- Wing and/or landing gear bolts or rubber bands

- Fuses

- Propellers and prop adapters

- Screwdrivers, wrenches, and Allen keys

- Packing tape

- CA glue

- Scrap balsa

- Ammeter or Whattmeter

- Tachometer

- Soldering iron and solder

- Electrical tape

- Expanded scale voltmeter (ESV)

- Cordless screwdriver

- Sunglasses

- Sun hat

- Sun lotion and bug repellent

- Gloves (for winter)

- Camera

- First aid kit

What’s in Your Field Box?

Well, I’ve told you what’s in my field box. I’d like to know what’s in yours. What pieces of equipment do you find essential? Also, what features of the box itself make it a great, or not so great, field box? Please e-mail me let me know. If there’s enough interest, I may attempt to design, build, and publish the perfect e-flight field box.

Related Articles

If you've found this article useful, you may also be interested in:

- Aviator Sunglasses

- Caring for Your Lead-Acid Field Battery

- Winter Electric Flight

- E-Flying at High Elevations

If you've found this article useful, consider leaving a donation in Stefan's memory to help support stefanv.com

Disclaimer: Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and reliability, the information on this web page is presented without warranty of any kind, and Stefan Vorkoetter assumes no liability for direct or consequential damages caused by its use. It is up to you, the reader, to determine the suitability of, and assume responsibility for, the use of this information. Links to Amazon.com merchandise are provided in association with Amazon.com. Links to eBay searches are provided in association with the eBay partner network.

Copyright: All materials on this web site, including the text, images, and mark-up, are Copyright © 2025 by Stefan Vorkoetter unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved. Unauthorized duplication prohibited. You may link to this site or pages within it, but you may not link directly to images on this site, and you may not copy any material from this site to another web site or other publication without express written permission. You may make copies for your own personal use.